Sustainable sugar alternatives

Sweetening the deal: Why natural-tasting, sustainable sugar alternatives could be just around the corner

In this article, we explore why we urgently need sustainable, healthy sugar alternatives, the limitations of current substitutes, and the next-generation startups poised to tap a sweet market opportunity.

Sugar is everywhere. It sweetens our drinks, softens our baked goods, preserves our food, and underpins vast swathes of the global food system. These functional advantages have fuelled a steady expansion in sugar use, driving a dramatic rise in consumption over the past century. Although this growth has slowed over the last two decades as health concerns have gained prominence, added sugars still account for a significant share of daily calorie intake. This makes them difficult to resist or avoid, given how deeply they are embedded in our modern food system.

The health implications of this sugar habit are stark. Excess sugar consumption is a major driver of the global burden of non‑communicable diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, which place enormous strain on health systems worldwide. These diseases reduce the quality of life of those afflicted and increase preventable healthcare costs and emissions. These impacts fall hardest on people with fewer resources, who often rely on affordable, sugar‑dense foods, thus worsening public‑health inequalities. Yet humanity’s sweet tooth also has a significant and underdiscussed climate impact.

Sugar sits at the centre of one of the world’s largest and most climate-intensive commodity systems. Although sugar is one of the highest-yielding crops by weight, producing enormous biomass per hectare, this productivity comes at a significant cost. Sugar cultivation takes over vast areas of land, contributes heavily to water pollution, and drives soil toxicity and acidification. Sugar cane production is also linked to deforestation and burning practices. These cultivation, processing, and land-use impacts create a substantial environmental burden, including greenhouse gas emissions, habitat loss, water scarcity, soil degradation, and air pollution. This cannot continue.

There is also a resilience aspect to Europe's urgent need to find a sustainable alternative to sugar. Cane sugar accounts for roughly 80% of global sugar production and is concentrated in Brazil and India, with beet sugar making up the remaining 20%. While around half of global beet sugar is grown in Europe, the continent remains reliant on imports to create the everyday foods that satiate the European population. In 2024/2025, the EU consumed about 16.8 million tonnes of sugar, compared with domestic production of approximately 14.8 million tonnes. This shortfall is met through regular imports of around 3 million tonnes. This dependence on external supply leaves Europe exposed to climate-driven disruptions in major exporting regions, adding another layer of risk to an already fragile supply chain.

Climate change is already affecting sugar production, exposing Europe to geopolitical tensions and potential supply chain issues. Yields of major crops, including sugar, are expected to fall further by 2050 as rising temperatures and extreme weather disrupt growing conditions. Cost is also a factor, with sugar prices having recently experienced the highest volatility in decades, with over 30% price swings within 12-month periods. This was recently exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic and drought-driven supply contraction.

Why sugar has been so hard to replace

So, if the incentives to find sustainable sugar alternatives are so clear, why has a solution not yet taken over the market?

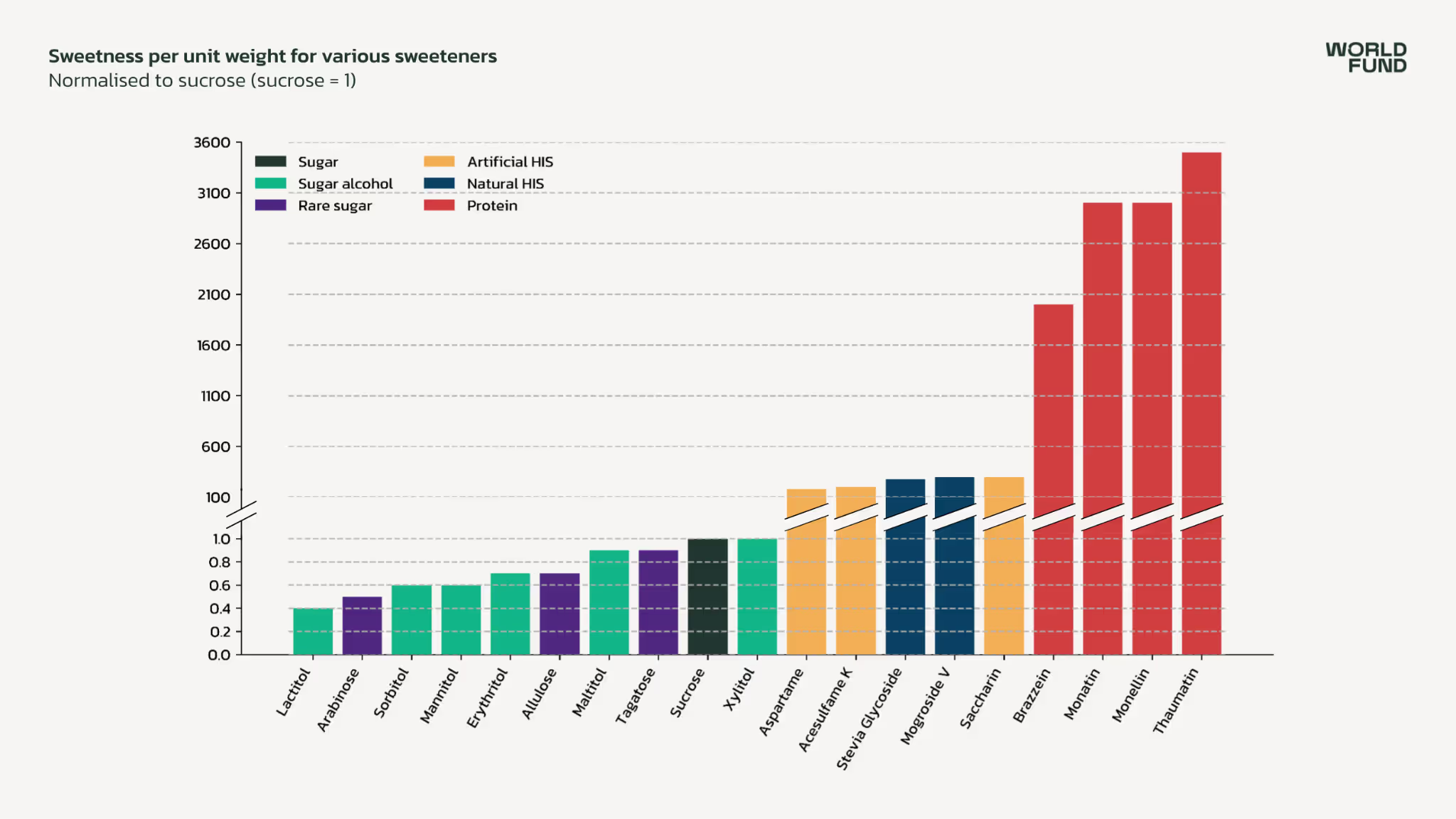

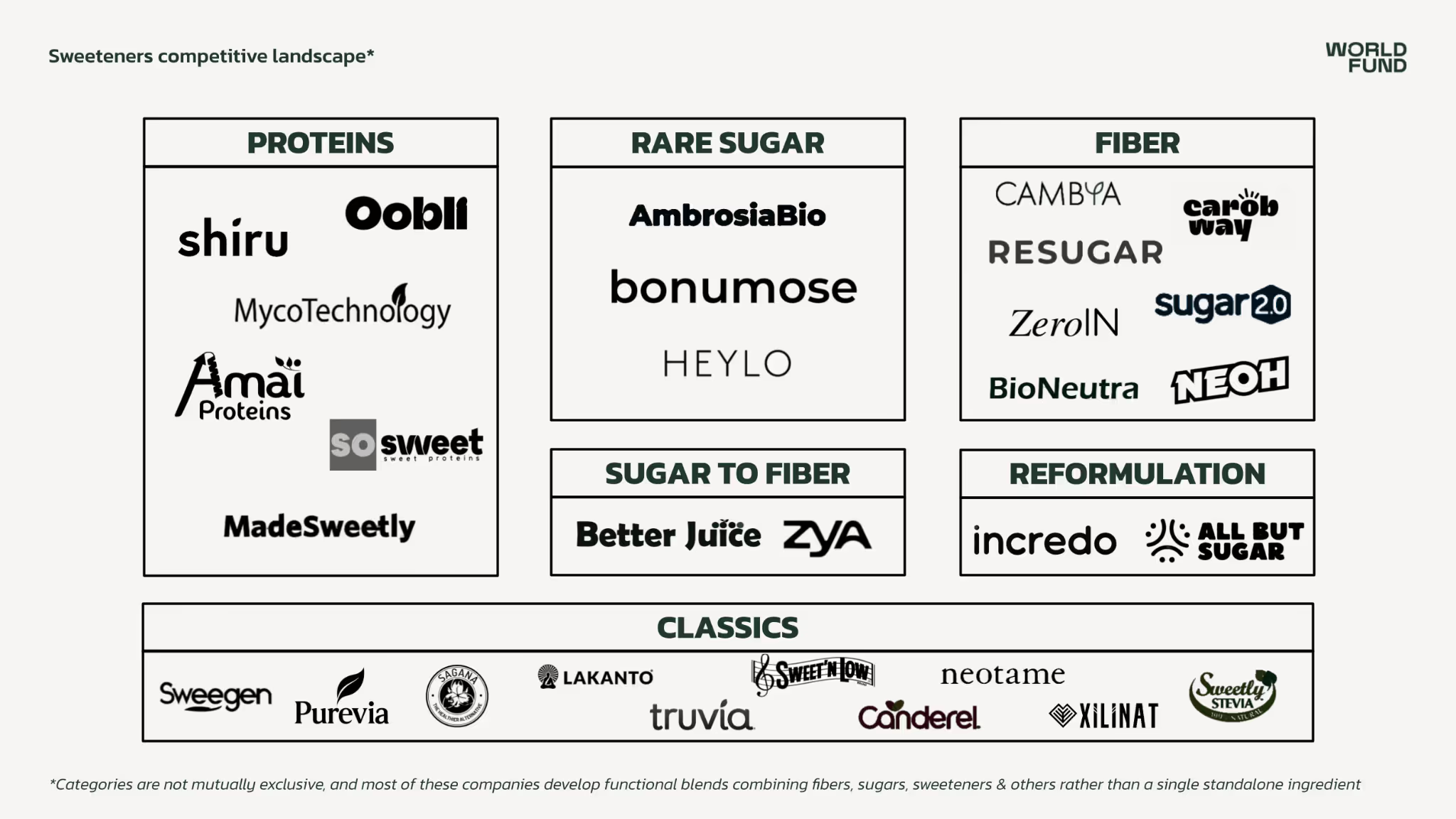

Companies have been trying for decades to create a product that replicates the exact taste, feel and after-effects of sugar, beginning with artificial sweeteners such as aspartame, acesulfame K, and saccharin in the 1980s and 1990s. These alternatives are still present in billions of products today, in addition to sugar alcohols like sorbitol and erythritol, and more recently, plant-based alternatives such as stevia and monk fruit.

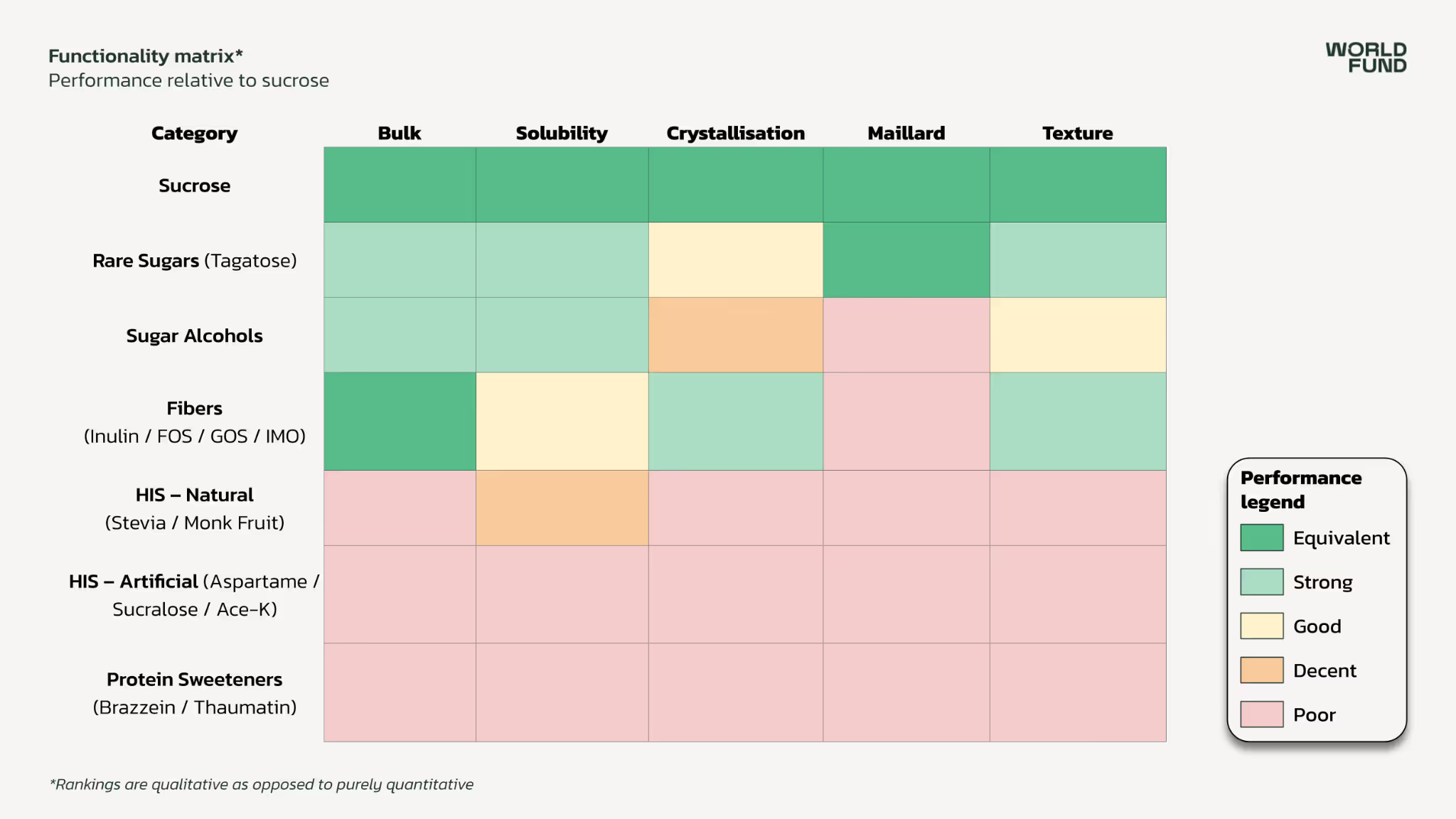

While these alternatives do have lower glycemic indexes (GI), as we have all experienced, they often come with a slightly off-putting aftertaste. In addition to taste, they have struggled to match the emotional pull and functional properties of sugar. Due to their structure, sugar molecules provide unique characteristics, such as bulk and viscosity, while also controlling crystallisation, retaining moisture, and stabilising shelf life by inhibiting microbial growth. Replicating this requires more than just sweetness. It demands compounds that can perform like sugar under heat, over time, and across complex formulations. Many traditional sugar alternatives are also now being proven to have negative health impacts. Aspartame, for example, has been linked to carcinogenic properties by the World Health Organisation.

However, the status quo is shifting as a host of sustainable, healthy sugar alternative producers are rising in Europe and around the world. These companies hope to tap a rapidly growing market driven by multiple health and sustainability factors, including rising consumer aversion to chemicals and ultra-processed foods (UPFs), as well as increasing regulatory pressure.

Sweet proteins, rare sugars and fibres: the next-generation sugar alternatives gaining traction

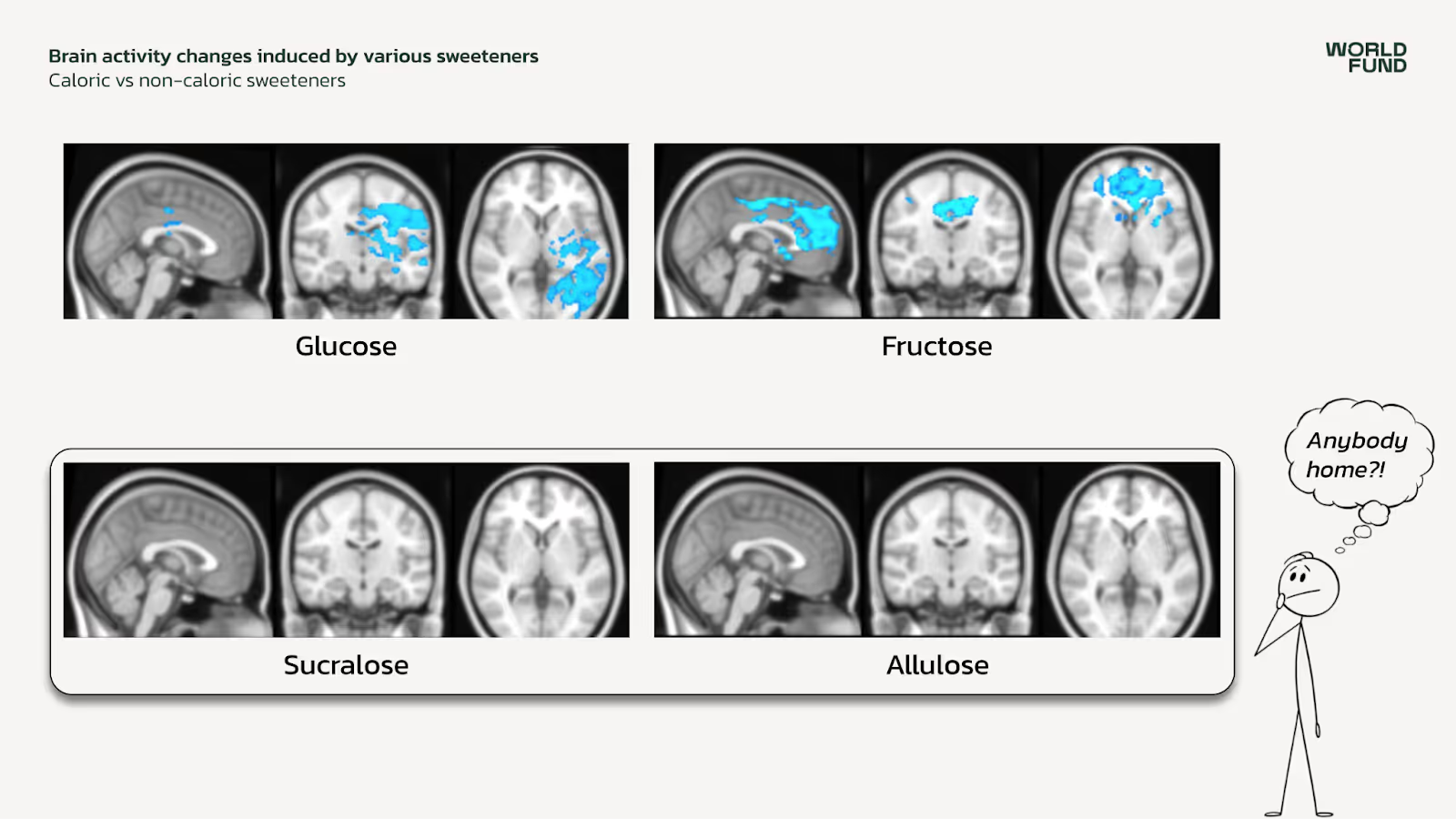

There is a clear scientific explanation behind our love of sugar. Sweetness is perceived through a specific receptor on the tongue, which triggers a response in the brain, leading to dopamine and beta-endorphin releases that create reward loops and dependency.

Until now, alternative sugars have not triggered the same responses. But recent advances in rare sugars, proteins, fibre-based alternatives, and enzymatic technologies represent a new opportunity:

Rare sugars (allulose, tagatose)

Pros: Rare sugars are exciting because they offer a close-to-sugar taste and functionality, while their chemical structure provides a lower calorie profile that does not trigger metabolic disease. Crucially, they are also a completely natural product found in low concentrations in fruit.

Cons: Since the rare sugar concentrations in fruit are so low (0.1% vs. 99% regular sugar), they remain expensive to produce and hard to scale. Unless they are derived straight from fruit, they also face regulatory hurdles.

Sweet proteins (brazzein, thaumatin, monellin)

Pros: These plant-based proteins can be up to 3,000 times sweeter than sugar, meaning only very small quantities are required in food products. They can be produced via precision fermentation or extracted from West African plant sources, which require minimal agricultural land due to their extreme potency, thereby reducing environmental impact.

Cons: Sweet proteins currently lack the functionality needed for processed goods and are primarily produced through expensive extraction or precision fermentation which is costly and limits access at current scale.

Fibres (inulin, FOS, resistant dextrins)

Pros: Fibres provide bulk and stability in food formulations while offering additional health benefits.

Cons: These fibres are only mildly sweet and cannot fully replace sugar, meaning they often need to be combined with other sweeteners. Over-reliance on fibres may also raise concerns around UPF content, limiting their appeal as a “natural” solution.

Enzymatic approaches (sugar: inulin-type fiber / prebiotic fiber)

Pros: Certain enzymes can convert a portion of sugar into non-digestible, inulin-type fibres or fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), either during food processing or, in emerging cases, during digestion, reducing effective sugar intake while preserving sweetness.

Cons: In vivo enzyme approaches are closer to a digestive aid or novel food ingredient, which can lead to long and uncertain regulatory pathways. Enzymatic modification may also raise questions about ‘naturalness’ and face scrutiny similar to that of additives or UPF-related technologies.

Many of the strongest early-stage platforms in proteins, enzymatic conversion and fibres, are emerging in the US and Israel. These include companies such as Oobli, whose sugar alternative is a sweet protein made through precision fermentation, and Bonumose, which is making strides with rare sugars. Oobli recently obtained later-stage FDA approvals for its process, a big step forward for the sector.

The European companies we’re excited about

In Europe, the sustainable sugar landscape remains a little behind that of the US. However, several early-stage European companies stand out. These include:

- Sweet Bliss (Denmark): Sweet Bliss is a very early-stage academic project developing a platform for designing and producing sweet proteins with versatile, functional properties tailored to specific needs. The company’s approach focuses on creating high-intensity, clean-label proteins for use in drinks, confectionery, and a range of baked goods. Although still early, the platform offers an exciting way to determine the sweetness of proteins in vitro quickly.

- Neoh (Austria): Neoh is developing a formulation-based functional blend combining fibres from agave, chicory and corn with sweeteners such as erythritol and stevia. It is already on the market and has a minimal impact on blood sugar. Its focus on bulk, clean-label positioning, and low-glycemic index (GI) aligns well with European consumer preferences.

- Yacon & Co (France): Yacon & Co offers a natural fibre-based sugar alternative made from Peruvian yacon root, a plant with a low GI and high fibre content. These fibres provide mild sweetness, strong functionality and metabolic advantages. With growing interest in fibre-forward formulation strategies, the company represents a practical near-term route to reducing digestible sugar content in confectionery and snacks. Notably, the company is based in France and is working to grow and process the yacon there to produce a 100% French-made product.

- Zya (UK): Zya uses enzymes to transform food after consumption, enhancing nutrition without compromising taste. The startup, based between London and Oxford, uses technology that converts sucrose into prebiotic fibre inside the body. By using traditional sugar, it hopes to reduce adoption barriers faced by alternatives.

These companies are all looking to tap an enormous and growing market. The global sugar market is worth around $75 billion today and is forecast to grow to over $120 billion by 2032, with a significant segment dedicated to sugar alternatives also expected to increase.

Where we see the greatest opportunity in sustainable sugar alternatives

All the European companies identified are promising, but several barriers remain, including cost concerns (no alternative is near price parity with cane or beet sugar) and regulatory hurdles. EU novel-food approval and US GRAS pathways can be slow, particularly for new proteins and enzymes. Consumer acceptance of these new alternatives is also an issue to consider, given that rising clean-label preferences matter, though evidence suggests consumers are more flexible in sweets than in other categories. We believe a realistic adoption curve will be gradual, beginning with mid-tier launches and reformulated SKUs before scaling into mainstream categories. We also believe that a real sugar alternative would need to be as sweet, as functional and as abundant as sugar while achieving a competitive price point.

At World Fund, we believe the greatest potential lies in next-generation functional blends of sweet proteins and fibres. No single molecule can replace sugar across all functions, and existing functional blends (fibres + polyols + flavours) often compromise on taste, texture, health and scalability. However, a combination of sweet proteins and fibres can deliver the full functionality of sugar molecules and a clean sweetness of taste while remaining low-calorie and low GI.

Our research also suggests that these blends have the clearest path to scalability and cost parity with sugar. They also show the strongest climate-impact profile. Compared with both traditional sugar and many existing sugar alternatives, sweet-protein and fibre systems can be produced through highly efficient precision-fermentation or low-input agricultural pathways. This enables significantly lower land and water use, reduced emissions, and the avoidance of the deforestation-linked footprint associated with cane and beet sugar.

If you are innovating in this sector, please get in touch with World Fund Principal Dr. Nadine Geiser at nadine@worldfund.vc.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)