Measuring the climate performance potential of startups

Measuring the climate performance potential of startups

As a climate tech VC we are driven to tackle the climate crisis by investing in climate technologies and solutions with both scale and significant emissions reduction potential. We believe that in a world that is increasingly complex and uncertain, measuring climate impact is not only crucial for the planet but also essential for identifying the next climate unicorn. Our thesis, summarised in one sentence, is this: Climate performance is a predictor of financial performance.

In recent years, we have worked with global leaders to stay at the forefront of climate measurement approaches, and have developed our climate performance methodology to transform qualitative into quantitative and artform into science. We have integrated this approach into our DNA across every facet of our operations and investment strategy. We aim for our methodology to be straightforward, scientific, and replicable. Let’s now talk about how we can leverage these assessments today and increase transparency into our methodology.

Does measuring climate performance work to identify climate unicorns?

From the very beginning, World Fund was deeply committed to measuring climate performance as a financial indicator, and while the data was still emerging at that time, our conviction drove us to lead the way in building that evidence. In 2025 we were finally able to put our hypothesis to the test. We pulled five years of climate data, from 2020-2024, and identified almost 150 climate tech unicorn companies over that time period. We then set about applying our methodology to these 150 companies aiming to assess how connected climate performance and financial performance was over those five years.

We found that over 60% of climate unicorns in Europe and the US passed our climate performance investment criteria of significant emissions reductions. This is especially meaningful when compared to standard dealflow, which has companies passing our assessment in the low double digits. We took this analysis a step further, and looked at the companies that went bankrupt within that timeframe. We found that over 80% of climate unicorns that filed for bankruptcy did not pass our climate performance criteria.

These results validate our hypothesis that climate performance goes hand in hand with financial performance, and additionally that our methodology could potentially contribute to risk mitigation. Obviously causation and correlation are not the same, but we find this data to be meaningful and indicative that we are using the right approach.

Nonetheless measuring climate performance can be challenging

To introduce best practices to estimate climate performance and advance climate investing, we first need to look at systems - which are multilayered, complex, and can be full of uncertainty.

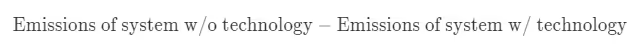

If you want to assess a technology’s, for example avoidable emissions over the next 20 years, you can rephrase that as:

or, equivalently, if we assume the evenly distributed impact per product on the system across time:

Our guiding principle is to assess the system with and without the climate solution measured over time. This includes assessing a technology’s product sales, the target market, the technology’s influence on that market, its climate footprint, and interrelations with other solutions.

All of this further depends on how our society will change in the future. Would you have predicted 20 years ago mass phenomena like social media or generative AI? Or a pandemic? We work to identify the best scientific consensus for industries, technologies and markets, and to ground our assessments with real data and scientific literature. This can sometimes be challenging when technologies are on the cutting edge of research. Our methodology is built to adapt to that uncertainty, and to recognize when it exists.

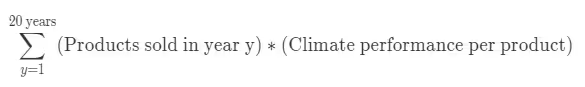

How to assess a startup’s climate performance potential

Assessing climate performance can be a complex task, which raises an important question: how should we approach it? Our view is that a pragmatic approach is essential. Below, we outline our perspective on how this can be effectively addressed today, given the current limitations

#1: Focus on one dimension first: the potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions

While the ideal scenario would involve multidimensional instruments for assessing climate performance, the reality is that each dimension presents significant challenges—most are data-sparse, complex, and difficult to evaluate. By far, the most mature KPI is the relationship of business impact (through product or supply chain) on the emissions of greenhouse gases. This increases the validity of these types of assessments. Further, the emissions of greenhouse gases are an excellent proxy for climate change mitigation, which adds to the reasons why this metric has the greatest data availability.

In other words, assessing the GHG drawdown potential of a startup allows us to determine, for example, that Startup A has the potential to avoid an order of magnitude more emissions than Startup B, and could therefore represent the more impactful choice.

This approach can be problematic if a startup’s primary impact dimension differs from this metric, or conversely, if the startup becomes overly focused on optimizing it. This leads us to the next pillar of assessment.

#2: Address other dimensions in a binary “do-no-harm” approach

For an investor, the minimum effort necessary to balance the focus on only emissions is a binary evaluation of other impact dimensions. It’s a more qualitative-type, but research-driven risk assessment, such as Impact Frontiers suggests. Concretely, this means: Which other climate-relevant areas will this startup touch once it scales? What unexpected second-order effects can we foresee? How do we assess the risk of doing significant harm in such an area? If significant harm is detected, this should influence the investment decision and the startup’s strategy.

#3: For early stage companies, go top-down on a more coarse, technology-level granularity to understand the strategic impact mechanics

Our recommendation is as follows: for early-stage companies, the focus should be on the underlying technology rather than the startup itself. Just as investors typically view sales forecasts of early-stage startups with caution, they should likewise avoid relying on impact forecasts at the startup level, as these are inherently dependent on sales projections. Instead, we assess the market and evidence-based technology adoption curves projected out to 2050.

We call this a volumes analysis. And it’s one of the main ingredients in measuring climate performance for early start ups. It requires going up a level in granularity to technology-level, which also includes technology competitors.

Why do we prefer this metric:

- It allows us to identify an exceptional technology bucket.

- Within that climate problem it helps select a technology we think will win. That’s typical for a VC, you don’t bet on competitors.

- Falling orthogonally into the set of classic VC decision criteria allows us to extend them cleanly instead of distorting and mixing them (which would increase bias and uncertainty).

By pairing a team’s execution capability with a near-competitive product in a climate-effective technology category, one can estimate the order of magnitude of potential returns in the event of success. For early-stage, pre-commercial products, this measurement is referred to as climate performance potential.

#4: For growth or commercial companies, focus on company specific granularity to understand the strategic impact mechanics

For more mature companies that are already operating commercially, we recommend conducting a thorough analysis of their commercial forecast.

Once companies are beyond R&D, past the pilot stage, and producing and selling their products into the broader commercial markets, they should have more robust commercial forecasts and business plans that can be assessed. It becomes crucial that not only the technology be impactful, but that they are able to execute and generate impact by commercializing quickly and reaching scale. This is similar to classic VC, where early stage companies are assessed on e.g. ideas, team construction and later stages are assessed on scale, execution, profitability over the hold period of the investment. Measurement for more mature commercial companies is called climate performance planned.

#5: Follow best practices to make assessments actionable

To allow better comparability and to benchmark for climate-effective decision making, it’s essential to follow certain best practices when using a tool, methodology, consultant for assessments:

- Consistency is critical for comparability, i.e., assumptions on projections & theory of change should be identical across different assessments

- Transparency on where assumptions and the data come from

- Conservatism is the safer choice when making assumptions

- Understanding the results and the mechanics of a specific evaluation by 1) using industry averages for key variables that are (for startups) unknown, 2) using realistic cases that aren’t only the best-case scenario for upper and lower bounds, and 3) minimizing the manifold of input variables, estimation errors multiply

#6: For evaluating short-term and historical performance, bottom-up assessments provide insight into the startup’s product mechanics

A startup is typically asset-light, and its primary lever is its product. Its vision is the reason for its existence. It is essential to understand the product mechanics and embodied emissions, as its production will have a significant impact as the company scales. This is done via a lifecycle assessment (LCA), typically an input value for a top-down assessment. LCAs traditionally are all about the product’s footprint instead of enabling effects. But for startups, there are also hybrid approaches that don’t comply with any scope but turn out helpful.

Once a per-unit LCA is established, which is called the unit impact, it can be multiplied by projected unit sales over a defined period to estimate the expected climate performance.

Limitations: Bottom-up assessments are generally better suited for evaluating the actual impact of a specific product. While this approach is valuable for reporting purposes, it also enables more precise short-term forecasts (typically 5–7 years). Additionally, analyzing product components can incentivize innovation and drive incremental improvements.

Towards creating a common lexicon to talk about climate performance

After speaking with numerous experts, we observed a shared and widely acknowledged ambitious vision for the future of climate performance assessments. They foresee that all classic financial instruments, from reporting to forecasting, will also be applied to non-financial climate dimensions:

- A transparent way of communicating and managing climate performance in multiple dimensions (CO2e, biodiversity etc.) through balance sheets, P&Ls, forecasts

- Best practice methodologies & standards allow benchmarking performance across industries and technologies.

- Investors, businesses, and consumers make strategic or simple buying decisions guided by indices for climatic performance.

Having a clearly defined ‘north star’ enables more coordinated and rapid progress. This has direct implications for the actions that can be taken today to accelerate this fast-evolving field. The following three strategies can support efforts across all of the areas mentioned above:

Demand (transparency on) climate performance KPIs

Make these assessments a requirement. As a VC, engage only with startups that provide a preliminary evaluation; similarly, request the same from co-investors. When governments or companies present new solutions, insist on receiving their climate-relevant KPIs. If such information is provided, seek transparency regarding data sources, methodologies employed, and related details.

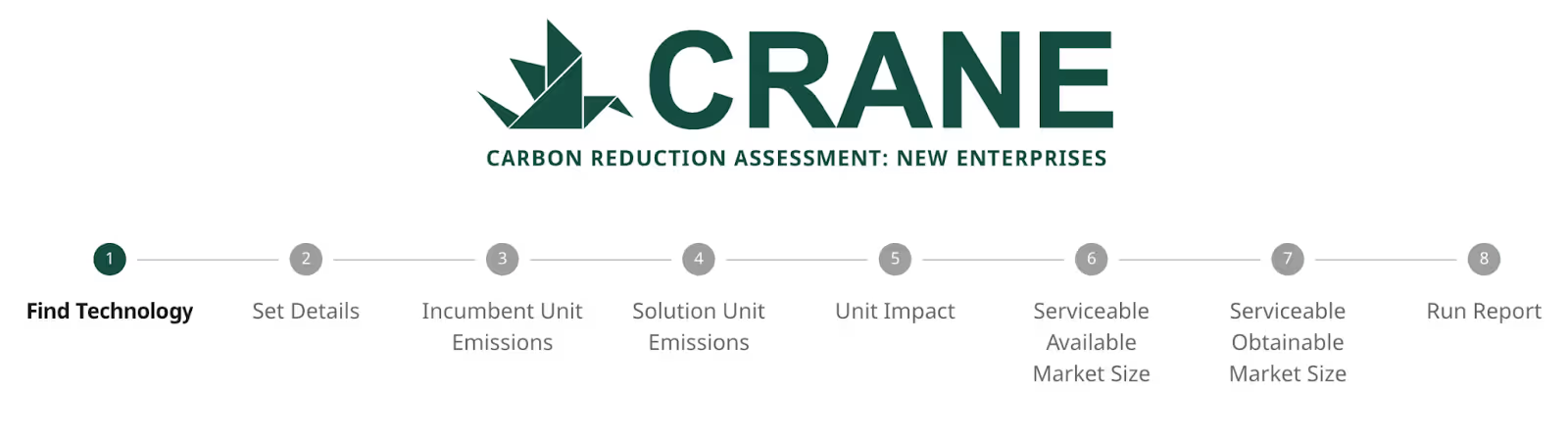

Check out the tools that exist or start your own

We are collaborating to create an overview of tools that exist in this space. Due to the shared vision and need for such tools, there are multiple tools driving decisions and directing significant amounts of money. You can find this database at the GHG Impact Resource Dashboard hosted by Project Frame.

Our goal is to empower the climate tech ecosystem to prioritize climate-effective execution. We are at the forefront of turning this vision into reality, enabling the climate tech ecosystem to make more informed decisions that benefit both the planet, resilience and financial returns.

---

Feel free to reach out to Morgan with any questions or follow ups at morgan@worldfund.vc.

About Morgan Sheil, Head of Impact, World Fund

Prior to joining World Fund, Morgan worked at Energy Impact Partners and KKR on sustainable investing, portfolio value creation, and technical and impact diligence. She began her career as an engineer at ExxonMobil. Further, she works on developing and authoring industry-wide impact methodologies and frameworks with Project Frame, the Venture Climate Alliance, and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development..

Morgan received her MBA from Harvard Business School, a postgraduate degree in sustainable systems engineering from University of Cambridge, and a degree in chemical and biomolecular engineering from the University of Maryland, College Park.

.svg)

.svg)

.jpg)

.svg)